3 min read

Komatsu supports reforestation at New River Gorge National Park and Preserve

- Sustainability,Blog,Social responsibility

12 min read

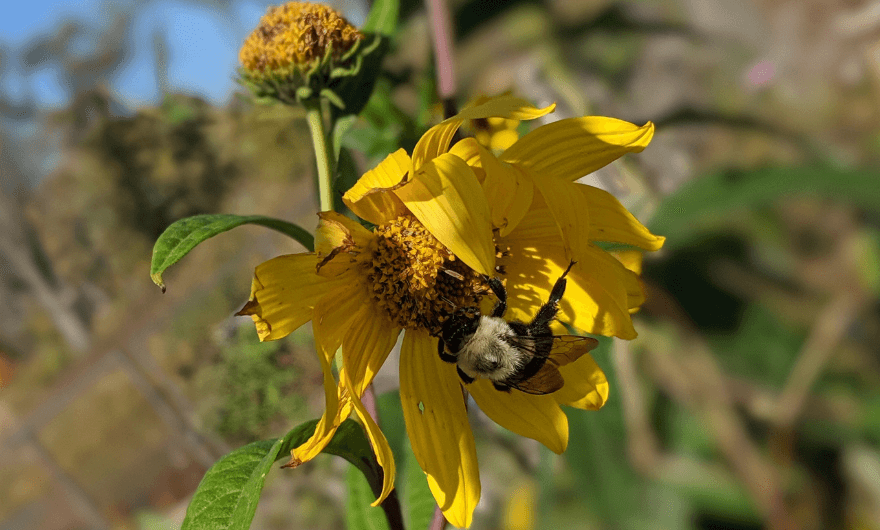

It might make you shudder, but imagine a world without coffee. Or, if caffeine isn’t your thing, what about a world without chocolate? Or cotton? Or aspirin? Apples, berries, cherries? Pumpkins, carrots, nuts? The list could go on and on.

What do all of these things have in common? They are dependent on one group of tiny and tireless creatures: bees.

Bees (and other pollinators) make it possible to grow everyday staples, like apples and almonds. Apples, in particular, need cross-pollination to grow. Without bees, humans would be left doing that pollinating work by hand – possible, but certainly not practical.

Did you know that bees pollinate one-third of all the food we eat?

And they make us money. Lots of money.

Worldwide, the global market value linked to bees and other pollinators is between $235 billion and $557 billion (U.S.) each year. In the United Kingdom, pollinated crops are valued at £691 million a year, while in the United States honeybees contribute an estimated $15 billion to crop production.

“Honey bees are like flying dollar bills buzzing over U.S. crops,” according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

A key link in the natural food chain, without bees, many herbivores would simply starve. And, without those plant-eaters, the meat-eaters above them would also falter.

Our bee friends, particularly wild bees, are also responsible for climate change mitigation. They are credited with fostering rich natural vegetation, which is known to offset carbon emissions.

“If all bees died, it may not be a total extinction event for humans, but it would be a disaster for our planet,” argues one bee blog. “We would see a domino-like effect as many plants started to just disappear one by one, and all animal species would start to struggle to find food.

“It's almost impossible to overstate how much bees play an essential role in the global food supply and natural balance of the planet. It's important not just for us that bees survive, but for every living thing on the planet.”

The United Nations agreed, and in 2017, they established May 20, as World Bee Day.

History of World Bee Day

The movement to give bees their own day started in 2014 in Slovenia, where one out of every 200 people keep bees and the history of beekeeping (or apiculture) dates back to the 18th century.

The Slovenian Beekeepers’ Association first proposed the idea of World Bee Day. A year later, the Slovenian government and Apimondia, the world’s largest international organization of beekeepers, joined the movement.

By 2017, the United Nations’ Economic and Financial Committee officially named May 20, World Bee Day – a resolution supported by all UN states and co-sponsored by 115 countries including the United States, Canada, China, Russia, India, Brazil, Argentina and Australia.

The world has been celebrating these prolific pollinators ever since.

Bee hotels

Once World Bee Day was established, classrooms and companies around the world began working in service to bees. That includes our own team of bee hotel builders. Last year for Earth Day – in honor of our esteemed environmental wing-men – a team of about 30 Komatsu employees in Belgium built bee hotels outside Komatsu Europe headquarters.

The project was an employee idea that took flight as the team began to understand the plight of bees, including the estimated 350 species of wild bees in Belgium.

“These wild bees do not sting and are needed to pollinate more than 80% of all agricultural crops,” explained Evi Reynaert, human resources and sustainability manager for Komatsu Europe. “With a bee hotel, you can give the bees a boost.”

Initial plans to craft a hotel in the shape of an excavator proved impractical, so, after an online search for a more traditional design, the team gathered bamboo stems, pinecones and wooden logs to provide nesting materials and create the various-sized cylinders that make up the hotels.

Employees in the warehouse helped with carpentry, adding small branches and leaves and drilling holes in wooden blocks for the structures.

On Earth Day, employees gathered in the sunshine to assemble their structures, which they were invited to take home and put on their terraces and in their gardens. A special grand hotel was commissioned for outside the Komatsu headquarters, where it was officially inaugurated during 100th anniversary activities in September 2021.

“Almost immediately we had our first guests!” Reynaert said.

Pollinators and pollination: Beyond bees

While bees have their own day, they’re not the only guests at the pollinator party. There are approximately 200,000 different species of animals around the world who act as pollinators for more than 180,000 plant species.

That includes about 1,000 vertebrates, like bats and hummingbirds, as well as invertebrates, such as butterflies, flies, beetles, moths and wasps. And, perhaps surprisingly, a handful of mammals, lizards and marsupials are categorized as pollinators, including black-and-white ruffed lemurs (the world’s largest known pollinator), blue-tailed day geckos (the primary pollinator of several rare island-based flowers) and honey possums (the world’s only truly nectar-eating, or nectivorous, marsupial).

Together, they pollinate about 75% of the estimated 1,300-plus plants grown around the world for food, beverages, medicine, spices, condiments and fabric. More than half of our diet of fats and oils, and nearly 90% of the world’s flowering plants and about 80% of the wildflowers in Europe are all thanks to pollinators.

So, how to do they work this environmental magic?

Simply put, pollinators carry pollen from one flower to another and can also do the same for seeds. So, that means pollinators also help make vegetables, such as cucumbers, green beans and tomatoes.

Technically, Simply put when pollen grains are transferred from the anthers (or male parts, also known as the part of the flower stamen where the pollen is made) of one flower to the stigmas (or female parts, aka the top of the flower’s “ovary”) of another. Some plants can pollinate themselves. The wind also helps carry pollen and seeds for other plants.

But most plants need help, which brings us back to our humble bumble (and other) bees.

Back to the bees

There are more than 20,000 known kinds of bees worldwide. An examination of bee-dom in the United Kingdom gives us a glimpse into their biodiversity.

In the U.K. alone, there are 270 recorded bee species – only one is the universally famous honeybee, and most of those are kept in managed colonies. The remaining numbers includes 25 bumblebee species and 220 types of bees that live alone, called solitary bees.

On the bee family tree, honeybees are the undisputed stars. Of course, they are known for their honey and their beeswax, but they also play a large part in pollinating plants and flowers and crops.

Honeybees are considered superorganisms because of their complex social structures and intimate interactions with their environments – and each other. Tens of thousands of bees can live in a colony, with one queen presiding over a population that is, typically, 90% female. The queen lays the eggs, and male drones fertilize those eggs. They are also icons of unflinching work ethic; a single honeybee can visit more than 2,000 flowers in one day.

But the bee spectrum would not be complete without the often-overlooked native bees. In North America alone there are more than 4,000 species of native bees – from cuckoo bees and carpenter bees to leaf cutters and sweat bees, who actually lick human sweat.

Very few native bees sting. Their colors range from the traditional markings of the fuzzy black-and-yellow bumblebee to the iridescent green of those tiny sweat bees to the metallic sheen of blue orchard bees. Some native bees measure just an eighth an inch, while others are more than an inch long. Many live alone and have a lifespan lasting only weeks; male mason bees are solitary and live for only two to three weeks (females live about six weeks). During their short lives, some native bees only venture a few hundred feet from home.

Unlike their managed, hive-thriving cousins, native bees are not typically domesticated, but they are equally important pollinators. Quietly and (just as) industriously as the famous honey bee, native bees spread the pollen needed to keep crops growing– and are credited for significantly supplementing the work of their fuzzier counterparts.

Bee decline: Where have all the bees gone?

Despite their essential role in the food chain, all bees are struggling.

Climate change, loss of habitat, pesticides, genetically modified farming and disease are all contributing to a decline in bee populations, to the point that some are even considered endangered. A few have already gone extinct. The rusty patched bumble bee (some call them the “teddy bears” of the bee world) are among the most famous endangered bees – and those in the most trouble. They have lost nearly 90% of their population since the 1990s and were the first bee to be placed on the endangered species list in the United States.

Even managed hives are vulnerable; some have experienced exponential losses over the last 60 years, with populations falling by nearly 50% in some places in the last five to 10 years.

There are several reasons bees are threatened.

Parasites, such as varroa mites, bite bees and infect them with deadly viruses. These mites are an invasive species that began spreading in the 1960s because of the global trading of bees.

Agricultural practices are also complicating bees’ lives. Pesticides are poisoning bees; neonicotinoid pesticides, also known as neonics, have been directly linked to bee declines. Scientists are exploring whether the pollens from genetically modified crops (or GMOs) are not only detrimental but, in fact, deadly to bees. Evidence suggests GMO pollen could cause entire colonies to collapse. Even monoculture farming (farming one only one crop at a time) is an issue, since it limits bees’ diets.

Commercial development has also led to bee decline. Paving meadows and the countryside to build stores and factories and apartments might be good for economic growth and alleviate housing shortages, but it leaves bees competing for diminishing territories.

Even ubiquitous practices, like maintaining a green lawn, can harm bees Those backyard dandelions so many see as eyesores are lifelines for bees. Cutting them down breaks their food chain, while spraying them with weed killers, like glyphosate – once heralded as “harmless” to animals – kills the flowers AND the bees.

Rising temperatures attributed to climate change have been especially jarring for bees. One study suggests climate change is even more detrimental to bees than losing habitat. Changing temperatures are also throwing off bees’ sense of timing, leading to lower body weights and earlier emergences in spring. Some theorize that bees are dying simply because they expend more energy as temperatures sway hotter and colder due to climate change.

The many ways to help – from bee hotels to bus stop roof gardens

So, what can we do?

Thankfully, the ways to help bees are almost as numerous as they ways in which they are threatened.

Individuals can make a big difference for bees by planting pollinator-friendly plants, drilling holes into wooden blocks to make “bee condos,” and avoiding pesticides. Even buying local, raw honey and not disturbing bee swarms – swarms are totally normal and natural – can help.

In the Netherlands, a designer used a 3D printer to make self-sustaining artificial flowers meant to feed pollinators for up to 10 years. Another Holland-based project planted gardens on bus stop roofs. Sedum flowers and other plants make up the innovative green roofs, which help absorb rainwater, capture pollutants from the air and help regulate temperatures. In addition to helping bees, they also reduce noise pollution, absorb carbon and just make things look lovely.

Scientists have created a first-of-its-kind map to track bee populations globally, which they believe will help us target conservation efforts in the future.

Corporations have also gotten involved. Some are inviting bee advocate groups, such as the Planet Bee Foundation, to help establish company beekeeping programs. While others, like ours have built their own bee hotels.

This year for Earth Day, the team in Belgium is adding a bee buffet to their hotel outside of Komatsu Europe headquarters.

“We have sown seeds around the bee hotel and on the terrains around our offices to create a sustainable garden,” Reynaert said. “It has several advantages: less maintenance than a lawn, beautiful and always different, attractive to many animal species, and nectar and pollen for happy bees!”

The entire bee hotel project has been an inspiration – one Reynaert and the team hope will inspire others.

“Help the bees!” she said. “We hope people take small actions in their own garden as well: insect hotels, wildflowers, not mowing the lawn that frequently. Those small actions that we all take can generate a big impact!”

Reynaert’s sentiment echoes what drove the push behind World Bee Day in the first place.

“It is time for everyone to listen to bees, in particular, leaders and decision-makers,” said Boštjan Noč, author of the World Bee Day initiative and president of the Slovenian Beekeepers’ Association. “I believe that – with the proclamation of World Bee Day – the world will begin to think more broadly about bees, in particular in the context of ensuring conditions for their survival, and thus for the survival of the human race.”

Learn more about Komatsu’s commitment to the environment and society.